CRYPTO TAX & REGULATIONS

ATO Crypto Rules: What Every Aussie Investor Needs to Know

Table of Contents

Introduction

Cryptocurrency has taken Australia by storm, and with it comes the tax man’s keen interest. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO Crypto rules) have been made clear that crypto investors must play by the rules when it comes to taxes. Whether you’re a casual Bitcoin HODLer, an NFT artist, or a high-frequency trader, it’s critical to understand how the ATO’s crypto tax rules affect you. This comprehensive guide breaks down everything – from capital gains on your trades to the nuances of staking income – so that both new and experienced crypto investors can stay informed and compliant.

In this guide, we’ll cover all the essentials of Australian crypto taxation in plain English. Expect clear explanations, examples, and actionable tips on minimising your tax legally. We’ll also point you to further resources (like our Cryptopedia lessons) for deeper dives into foundational crypto topics where needed. By the end, you’ll have a superior grasp of ATO crypto rules – making this your go-to resource Australia-wide for crypto tax knowledge.

Important Note: Tax rules can change, and while this guide is up-to-date as of 2026, always stay informed on the latest ATO announcements. When in doubt about your personal situation, consider reaching out to a crypto-savvy tax professional (our team at Shepley Capital is always here to help with consultancy). Now, let’s dive in!

Crypto Assets and Tax Basics

What Is Cryptocurrency in the Eyes of the ATO?

For tax purposes, the ATO does not view Bitcoin or other crypto as “money” or foreign currency. Instead, cryptocurrency is treated as a form of property or an asset – much like a share or investment property. In fact, the ATO often uses the term “crypto assets” to encompass cryptocurrencies, tokens, stablecoins, and even NFTs. This means that general tax principles for assets apply to crypto. There are no special tax loopholes just for Bitcoin or Ethereum – how you’re taxed depends on how you acquire, hold, and dispose of the crypto asset.

Capital vs. Revenue: A key concept in taxation is whether a transaction is on a capital account (an investment) or revenue account (income/business). Most everyday crypto investors hold their coins as investments (capital), meaning that when they dispose of those coins, any profit is subject to Capital Gains Tax (CGT). However, some crypto transactions – especially those where you earn crypto – can be treated as revenue and taxed as ordinary income. We’ll explore both scenarios in depth.

If you’re new to how cryptocurrencies themselves work (blockchains, wallets, etc.), consider browsing our Cryptopedia explainer on “What is Cryptocurrency?” for a solid background. It’s important to have a basic grasp of crypto concepts, but for this guide we’ll stick to the tax treatment side of things.

How the ATO Tracks Crypto Transactions

Worried that your crypto activity flies under the radar? Think again. The ATO has sophisticated data-matching programs and agreements with cryptocurrency exchanges (both Australian and many overseas platforms). In fact, exchanges and other crypto “Designated Service Providers” regularly report user transaction data to the ATO. This means the ATO can often see when you buy, sell, or trade crypto, the amounts, and even which wallet addresses are involved.

Starting in recent years, the ATO has requested information on over a million Australian crypto investors – including personal details (name, DOB, address) and transaction histories – to ensure people are meeting their tax obligations. This process is commonly referred to as Know your Customer (KYC). Many investors have received “please explain” letters reminding them to report crypto gains. Bottom line: assume the ATO knows about your crypto dealings, and always declare your taxable transactions. Crypto is far from anonymous when it comes to tax.

On the upside, being aware of ATO’s oversight can motivate you to keep excellent records and report correctly. The last thing you want is to ignore crypto taxes and later face an audit, penalties, or a hefty tax bill. Remember, in Australia tax evasion is a serious offense. So transparency and compliance are the best policies.

Investor or Trader? (Tax Status Matters)

One of the first things to determine is whether you are treated as a crypto investor or a crypto trader for tax purposes. The distinction is important:

- Investor: If you’re buying crypto as a personal investment, hoping it will appreciate over time or using it as a store of value – you’re likely considered an investor. Investors are subject to CGT on profits from disposals, and can potentially access the 50% CGT discount (more on that later) for long-term holdings. Most hobbyist and casual crypto buyers fall in this category.

- Trader (Business): If you are running a business of trading crypto – for example, frequently buying and selling with the intention of making short-term profits, or you operate a crypto exchange or mine crypto at scale, the ATO may treat you as carrying on a business. In that case, your crypto is treated like trading stock (inventory) and profits are taxed as business income (no CGT discount, but business deductions apply). Traders are typically those with high volume, a profit motive, business plans, and a “business-like” operation (keeping books, having an ABN, etc.).

The line can be fuzzy, but generally it comes down to intent, repetition, and scale. A few trades a year with long holding periods? Likely an investor. Daily short-term trades with significant capital at play? You could be viewed as a trader.

Why it matters: An investor will calculate capital gains or losses on each disposal and pay tax on net gains at their income tax rate (with potential discounts). A trader will treat crypto profits as ordinary income and can deduct related expenses; crypto held at year-end is accounted for like stock on hand. Traders do not get the CGT 50% discount for holdings over 12 months.

If unsure where you stand, it’s wise to consult a tax professional. Misclassifying yourself could mean paying too much tax – or not enough (raising red flags). Our Shepley Capital consultants can review your situation if needed. You can get in touch with a member of our team here: shepleycapital.com/strategy-call

Table: Investor vs Trader – Tax Treatment Overview

Criteria | Investor (Capital Account) | Trader (Business/Revenue Account) |

Typical activity level | Occasional trading or long-term holding | High-frequency trading or operating a crypto business |

Intention | Long-term investment, wealth growth | Short-term profit, operating for income |

Tax on profits | Capital Gains Tax (on disposal events) | Income Tax (business revenue) |

CGT Discount (≥12m held) | Yes, 50% for individuals (if held over 1 year) | No (not applicable, gains are ordinary income) |

Treatment of losses | Capital losses (can offset capital gains only) | Revenue losses (can offset other income in business) |

Deductible expenses | Limited (cost base includes some costs) | Broadly yes (business expenses deductible) |

Examples | Casual investor, long-term HODLer | Day trader, crypto mining business, exchange operator |

Most readers of this guide will be investors, not professional traders, so much of our focus will be on capital gains rules. But keep the distinction in mind – if you start trading at scale or mining with expensive rigs, your tax treatment could shift into business territory.

For additional information directly from the official ATO website, check out ‘how to work out and report CGT on Crypto’ here.

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) on Cryptocurrency

If you’re holding crypto as an investment (personal or in a self-managed super fund, etc.), then Australian Capital Gains Tax rules are at the heart of how your crypto is taxed. The term “CGT” actually refers to the framework for taxing capital gains, and it’s not a separate tax – capital gains are included as part of your income tax.

Let’s break down the key points of CGT for crypto:

What Counts as a CGT Event for Crypto?

A CGT event is essentially a trigger that causes you to realize any capital gain or loss on an asset. For crypto assets, a CGT event typically occurs whenever you dispose of your cryptocurrency. Importantly, “dispose” doesn’t just mean selling for Australian dollars. According to the ATO, a disposal happens when you change ownership of the asset. Common crypto CGT events include:

- Selling crypto for fiat currency: For example, cashing out Bitcoin to AUD. This is a disposal at the moment of sale.

- Trading or swapping one crypto for another: Exchanging ETH for BTC, or even swapping crypto for a stablecoin like USDT, triggers a CGT event. You are disposing of one asset (ETH) to acquire another (BTC). Many people don’t realize this is taxable because no cash changes hands – but the ATO treats it as if you sold ETH for its market value and bought BTC.

- Using crypto to purchase goods or services: If you pay for a new laptop with crypto or use a crypto debit card, you’ve disposed of that crypto. The ATO considers that a sale of the crypto at its market value on that day (which you used to “buy” the item). So yes, spending crypto can incur CGT.

- Gifting crypto to someone: Giving crypto away is treated as disposing of it at market value on the date of the gift. Even though you didn’t “sell” it for money, you have a CGT event (with proceeds equal to the asset’s value at the time you gifted it).

- Exchanging crypto via peer-to-peer or OTC trades: Any transfer of ownership, whether through an exchange, P2P marketplace, or directly with another person, is a disposal for tax purposes.

On the other hand, some actions are not disposals:

- Simply buying crypto with fiat is not a CGT event (though keep records).

- Transferring crypto between your own wallets (with the same beneficial owner) is not a disposal, provided you’re not changing ownership – we’ll cover nuances like network fees later.

- Holding crypto without selling/trading doesn’t trigger tax; you can watch your portfolio go up and down all day without tax implications until you dispose of something.

One special note: if your crypto is deemed a personal use asset, some disposals might be exempt. But that’s a very limited scenario for most investors and we’ll address it later.

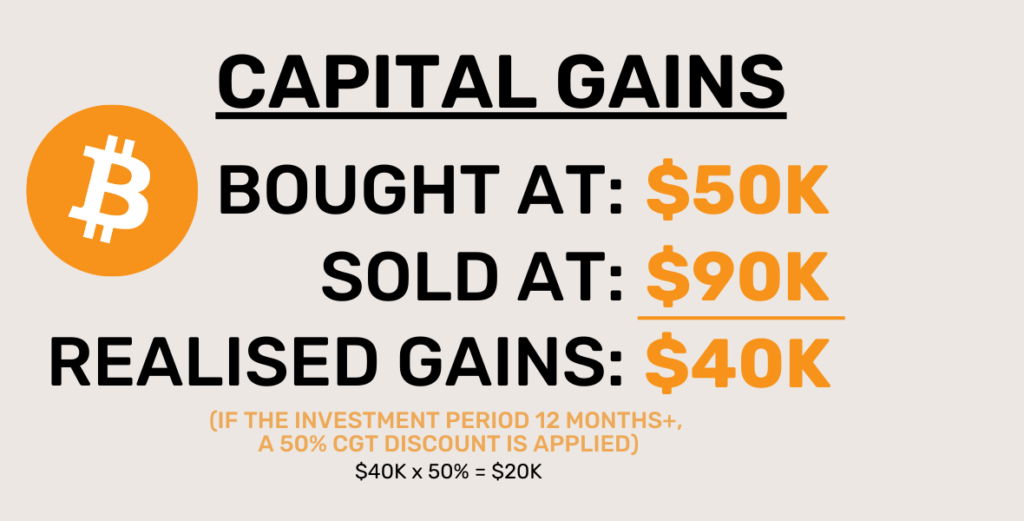

Calculating Capital Gains and Losses

Whenever a CGT event occurs, you’ll need to calculate the capital gain or loss. In simple terms:

- Capital Gain = (Value of crypto at disposal) – (Cost base of crypto)

- Capital Loss = (Cost base of crypto) – (Value at disposal), if positive.

The “cost base” of your crypto is essentially what it cost you to acquire it, plus certain costs associated with acquiring or disposing of it (for example, exchange fees, broker commissions). All values should be in Australian dollars (AUD). If you originally bought crypto in another currency or received it at a certain AUD value, that’s your starting cost.

Example (Simple): Alice bought 1 Bitcoin for $30,000 in 2023. In 2025, she sells that 1 BTC for $50,000. Her cost base = $30,000 (assuming negligible fees for simplicity). Her proceeds = $50,000. Capital gain = $50,000 – $30,000 = $20,000. This $20k will be added to her taxable income (although discounts might apply if it was held >12 months).

Example (With Crypto Swap): Bob traded 2 ETH for 1 BTC. At the time of trade, 2 ETH were worth $6,000 total. Bob originally bought those 2 ETH for $4,000. In the swap, Bob’s proceeds for disposing of ETH are $6,000 (the market value, which equals the cost of the BTC he received). His cost base was $4,000, so he has a $2,000 capital gain on the ETH disposal. For the new BTC acquired, Bob’s cost base is $6,000 (what he effectively paid). When Bob eventually sells that BTC, he’ll calculate gain/loss relative to $6,000.

Tracking cost bases: Crypto can involve many transactions, so keeping track of each purchase lot and its cost is crucial. If you have multiple units of the same crypto bought at different times (e.g., you dollar-cost averaged into Bitcoin throughout the year), you have a few options in Australia for determining which units you sold:

- You can specifically identify the units you are disposing of (if you have records). For instance, if you have 1 BTC bought in January and 1 BTC bought in June at different prices, you can choose which one you’re “selling” if you sell 1 BTC – assuming you can identify them via records like wallet addresses or transaction IDs.

- If you don’t specifically identify, a common method is FIFO (First-In First-Out) – meaning the first coins you bought are treated as the first sold.

- The average cost method can be used in some situations (like if assets are pooled), but there are restrictions and it’s less common with crypto due to distinct units.

The ATO allows you to use any reasonable cost basis method as long as you’re consistent and have evidence. Many investors use software to track this. The key is that for every taxable disposal, you need a clear cost base and sale value in AUD.

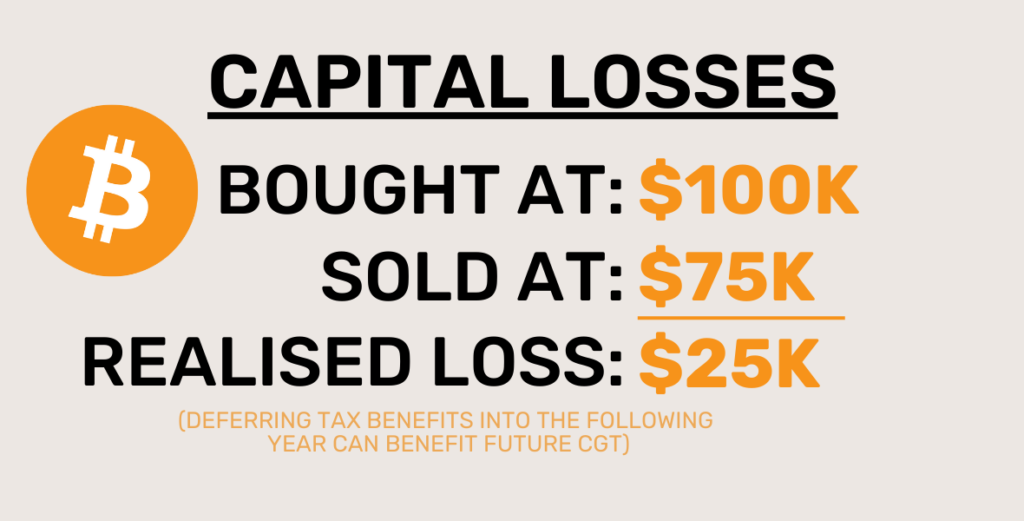

Capital losses: If your disposal proceeds were less than your cost base, you have a capital loss. Don’t panic – while losses don’t get you an immediate refund, they are valuable in that:

- You can use capital losses to offset capital gains (reducing your taxable gains).

- If you have more losses than gains in a year, the excess loss is carried forward indefinitely. You can use it in future years to offset future capital gains.

- Capital losses can only offset capital gains, not other types of income (unless you’re a business trader, different rules). So you can’t use a crypto capital loss to reduce your salary or interest income in that year. It only comes into play when you have capital gains.

Make sure to use your losses at the first opportunity – if you have carryover losses and then make a gain, you must apply the loss against that gain before applying any discounts.

For more examples of CGT realised gains/losses, access our “Capital Gains Tax for Cryptocurrency in Australia” educational resource.

Capital Gains Tax Rates and Discounts

Australia doesn’t have a separate CGT rate schedule; instead, any net capital gains you realize in a year are added to your assessable income for that year. That means the tax on your gain is determined by your income tax bracket in the year of the gain.

For example, if your taxable income (including crypto gains) puts you in the 32.5% marginal tax bracket, your crypto gain effectively gets taxed at 32.5%. If you’re in a higher bracket, it could be 37% or even 45% for top earners. Conversely, retirees or low-income individuals might have a lower marginal rate. (As of 2025, Australia’s tax brackets were set to change, with a 30% flat rate for middle incomes up to $200k, etc., but the exact rate you pay will depend on current law and your income.)

The 50% CGT Discount: One of the biggest tax perks for investors is the 50% discount on capital gains for assets held at least 12 months. This rule means:

- If you buy and then later sell the same crypto after holding it for 12 months or more, any gain is halved for tax purposes. In other words, only 50% of the gain is added to your taxable income.

- This discount is only for individuals and trusts. (Super funds have a 1/3 discount after 12 months. Companies do not get any CGT discount at all.)

This is a huge incentive to be a long-term investor rather than a rapid flipper, at least from a tax perspective. For instance, imagine you made a $20,000 gain on Bitcoin. If you held the BTC for over a year, only $10,000 would be taxable. If you’re in a 37% bracket, you’d pay about $3,700 tax instead of $7,400 – a significant saving.

If you’re just shy of the 12-month mark, consider holding on a bit longer to qualify, assuming market conditions allow and it fits your investment plan. But note that the 12 months is measured from purchase date to disposal date (the dates count; check exact days).

Short-term gains (held less than 12 months) get no discount – 100% of the gain is taxable.

Also, note that capital losses are applied before the discount. So if you have gains and losses, you subtract losses first, then apply the 50% discount on the remaining gain.

Using and Deferring Capital Losses

Crypto markets can be volatile, and many investors have experienced losses – whether from selling in a downturn or coins going to zero. The silver lining is those capital losses can soften your tax burden:

- Offset current year gains: If in the same tax year you have some winning trades and some losing trades, you subtract your total losses from your total gains. Tax is only on the net gain. For example, $10k gains and $7k losses result in $3k net capital gain taxable.

- Carry forward unused losses: If your losses exceed your gains in a year, you won’t pay CGT (since net gain is zero or negative). The remaining net capital loss carries forward. There is no time limit – it can be carried forward indefinitely until you have gains to use it on. However, you must keep track and use it at the first opportunity. You can’t selectively save losses for a later year if you had gains this year – you must use losses as soon as possible.

Deferring gains vs “loss harvesting”: Some investors try to strategically time gains and losses:

- If you have big unrealized gains near the end of the financial year (say in June), you might wait until July (the new tax year) to sell, effectively deferring the tax on that gain to the next financial year. This could be useful if it keeps your income lower for the current year or if you expect to be in a lower tax bracket next year.

- Conversely, if you have losses, you might choose to realize them (sell the asset) before year-end if you need to offset other gains in that year. Realizing losses intentionally for tax benefit is often called tax-loss harvesting.

There is nothing wrong with sensible timing of sales for tax purposes. However, be very careful of engaging in a wash sale – an artificial loss where you sell an asset purely to claim a loss and then buy it back immediately. The ATO has explicitly warned against wash sales. If you sell crypto on June 29th to crystallise a loss and buy the same crypto again on July 1st, thinking you tricked the system, the ATO may deny the loss deduction and penalise you. The rule of thumb is: don’t repurchase the same or similar asset within a short window just to dodge taxes. Real losses from genuine changes in investment are fine to claim, but don’t abuse the system.

Example – Offsetting: Carol has a $5,000 capital loss from selling some altcoins at a dip. Later in the year, she has a $8,000 gain from selling part of her ETH holdings. She can offset the $8k gain with the $5k loss, leaving a net $3k gain. If that ETH was held over 12 months, the $3k is then halved (50% discount), so she only adds $1.5k to her taxable income.

If Carol had no gains this year, the $5k loss is not wasted – it carries to next year. Suppose next year she makes a $10k gain on another trade (with no other losses). She can bring forward the $5k prior loss, offset it, leaving $5k gain taxable (or $2.5k if long-term discounted).

Always keep documentation of your losses (trade records, exchange statements) in case the ATO asks for proof.

The Wash Sale Rule (Don’t Cheat the System)

As mentioned, a wash sale is when someone disposes of an asset to claim a loss, but in substance they haven’t really changed their position. Typically this involves selling and rebuying the same asset in a short time frame. The ATO views this as tax avoidance.

With crypto, wash sales might involve selling coins at a loss and buying back the same coin (or a coin with very similar characteristics) immediately or through a different account or a spouse’s account.

The ATO has stated clearly that if you engage in wash sales to artificially create losses, they can negate the loss and apply penalties. There’s no fixed “30-day rule” like in some countries; it’s based on intent in Australia. If your intent was to create a deductible loss without really parting with the investment, it’s problematic.

Rule of thumb: Only realise losses for genuine portfolio reasons. If you sell for a loss, ideally stay out of that asset for a while (or accept the risk you might miss a short-term bounce). Or, if you want to maintain exposure, some investors might switch into a slightly different asset (e.g., sell one crypto and buy another – that’s not a wash sale, it’s actually changing investment). The key is not to end up in the same economic position immediately after just to get a tax benefit.

Always remember, the ATO can disallow artificial or contrived transactions. It’s not worth trying to game the system – you’ll likely lose in the long run.

When Crypto is Taxed as Income

Not all crypto gains come from buying low and selling high. In the crypto world, you might earn cryptocurrency in various ways – and when you do, it often is taxed as ordinary income rather than a capital gain. This section covers scenarios where crypto is treated like income (similar to salary, interest, or business earnings).

Earning Cryptocurrency (Staking, Mining, Airdrops, Salary)

Here are common ways you might earn crypto and their tax implications:

- Staking Rewards: If you stake coins (lock them up to help validate a Proof-of-Stake network) and receive new tokens as rewards, those rewards are typically ordinary income. The ATO’s view is that staking rewards are akin to earning interest or a reward for providing a service. You should declare the fair market value in AUD of the staking rewards at the time they are received (or when they become at your disposal). That amount is added to your assessable income for the year. It also becomes the cost base of those rewarded tokens for future CGT purposes. (Note: There is some ambiguity for cases like ETH2 staking where rewards were locked – when exactly you “derive” the income – but as of 2025 no specific ATO rule addresses that, so a conservative approach is to treat them as income as they accrue/are credited.)

- Mining Cryptocurrency: Tax treatment depends on scale:

- Hobbyist mining (e.g., you mine some coins at home on your PC for fun, not as a business) – the ATO tends to treat the mined coins not as immediate income but as having been acquired at the time of mining for a cost base potentially equal to any expenses or zero. When you eventually sell them, you pay CGT on the full amount (with cost base being effectively what it “cost” you, often just the electricity/computer depreciation that was not claimed). You also cannot claim mining expenses as deductions if it’s a hobby.

- Mining as a business – if you have a serious mining operation (significant hardware, electricity bills, an intention to profit), then it’s likely a business. In that case, the crypto you mine is trading stock or business output. The mined coins’ market value is included in your income when you receive them, and you can deduct related costs (rigs, electricity proportion, etc.). Future sales of mined coins are also treated on revenue account.

- Many miners start as hobbyists and then grow. If unsure, talk to a tax advisor because the difference changes how you report your crypto.

- Hobbyist mining (e.g., you mine some coins at home on your PC for fun, not as a business) – the ATO tends to treat the mined coins not as immediate income but as having been acquired at the time of mining for a cost base potentially equal to any expenses or zero. When you eventually sell them, you pay CGT on the full amount (with cost base being effectively what it “cost” you, often just the electricity/computer depreciation that was not claimed). You also cannot claim mining expenses as deductions if it’s a hobby.

- Airdrops: An airdrop is when you receive free tokens (often as part of a marketing push or for holding another token). The ATO updated guidance on airdrops: In most cases, airdropped tokens are treated as ordinary income when you receive them, valued at the market price on that day. You declare that value as income. There is an exception for certain “initial allocation” airdrops – where tokens were not trading and had no market value at the time of the drop (for example, you got an allocation of a brand new token that wasn’t yet on exchanges). In those cases, the ATO says the airdrop isn’t taxed on receipt (since no ascertainable value); effectively you treat the tokens as having a cost base of zero or whatever you paid, and only pay tax when you dispose of them later. This is a niche case; when in doubt, assume airdrops = income.

- Example: You receive 100 XYZ tokens in an airdrop and on that day each is worth $5 (so $500 total). You should report $500 of other income. If you later sell the 100 tokens for $800, you’ll have a capital gain of $300 (selling $800 minus $500 cost base).

- If the airdrop had no market value on receipt (not yet tradeable), you wouldn’t report income. Say a month later it lists on an exchange – at that point, arguably you might treat the value as income when it becomes tradeable, but ATO hasn’t explicitly stated this scenario. It’s wise to get advice if dealing with such cases.

- Example: You receive 100 XYZ tokens in an airdrop and on that day each is worth $5 (so $500 total). You should report $500 of other income. If you later sell the 100 tokens for $800, you’ll have a capital gain of $300 (selling $800 minus $500 cost base).

- Salary or Wages in Crypto: If an employer pays you in Bitcoin or any crypto, it’s still salary for tax purposes. The income is valued in AUD at the time you receive it and you’ll pay income tax on it just like if you were paid in cash. You might hear about salary sacrificing into crypto; technically, if done correctly, that could be treated as a fringe benefit arrangement. For most people, just know that being paid in crypto doesn’t avoid any tax – it’s simply converting your after-tax salary into an asset immediately.

- Businesses paying employees in crypto have to meet certain withholding and reporting obligations as well.

- If you’re a freelancer and a client pays you in crypto, that payment is your business income at market value on that day.

- Businesses paying employees in crypto have to meet certain withholding and reporting obligations as well.

- Referral Bonuses, Airdrop Campaigns, etc.: If you get coins for referring friends to an exchange or for completing some tasks (like “learn-and-earn” campaigns), those coins are considered income at their value when you receive them. Treat it similar to airdrops/interest.

Essentially, any time crypto “falls into your lap” as a result of some effort or service you provided, think of it as income. The crypto you earn will have an AUD value – that’s taxable. Later, if you hold that crypto and it changes in value, any further change from that point is a capital gain or loss when you dispose of it.

Crypto Business Activities vs. Personal Investment

We touched on the investor vs trader distinction. Let’s elaborate on some activities that might tilt you into business territory:

- Running a crypto exchange or ATM service – definitely a business.

- Engaging in full-time trading with substantial capital, maybe algorithmic trading, etc. – likely a business of trading.

- Large-scale mining farm or staking-as-a-service operation – likely a business.

- NFT creation: If you regularly create and sell NFTs (for example, you are a digital artist continuously selling NFT art), the ATO could view that as running a business or at least a profit-making venture. The income from selling your own created NFTs is likely ordinary income (just like selling artwork or content).

- Crypto lending or DeFi protocol operations: If you professionally run nodes, provide liquidity as a business, or operate a DeFi platform for profit, that could be business income.

If you are in business:

- Crypto transactions might be on revenue account: profits taxed as income, losses can potentially be deducted against other income.

- The crypto you hold for the business is treated as stock: end of year, you might need to value unsold crypto inventory (choose lower of cost or market or some method) to include in the business’s profit calculations.

- No CGT discount, no personal use exemptions, etc. – those are for personal investment.

- But you can deduct all the necessary expenses (equipment, electricity, internet, professional fees, etc.).

Example: If you’re a crypto day trader running through hundreds of trades, you might register an ABN, possibly even incorporate a company, and treat your activities as a business. If one year you incur a loss (net trading loss), that could potentially offset other income (like if you had a part-time job) – something capital losses cannot do for investors.

However, don’t rush to claim you’re a business just to deduct a loss. The ATO will look for the hallmarks of a business: continuity, repetition, a profit intention, significant effort and capital, and a business-like manner of operation. If those aren’t present, they won’t accept a “business loss” claim.

For most readers investing on the side, staying within the investment realm is simpler and often more tax-advantaged (thanks to the CGT discount).

In summary, know which bucket you fall into. And remember, you can be both: e.g., you might invest personally and also have a separate crypto mining business. But you’d need to clearly separate those activities and their accounting.

For any additional information regarding Capital Gains Tax in Australia, see the official ATO website.

Taxable Crypto Transactions Explained

In this section, we delve into various common (and some not-so-common) crypto transactions, explaining their tax treatment under ATO rules. Consider this your quick reference on “Is this crypto move taxable, and how?”

Buying and Selling Cryptocurrency

- Buying crypto with AUD (fiat): Not taxable. Purchasing Bitcoin or any crypto with Australian dollars (or any fiat) does not trigger a tax event. There’s no gain or loss yet – you’re simply converting cash to an asset. Also, since 2017, cryptocurrency is treated as input-taxed for GST (no GST on purchase/sale of crypto itself), so you don’t pay GST when you buy crypto either. However, keeping accurate records of the purchase is very important so that you can calculate the cost base of the transaction when you decide to sell or ‘dispose’ of your crypto, as that is the moment when you will have to pay tax.

- Buy and Hold: If you simply buy and hold your crypto, then you don’t need to pay tax on the cryptocurrency you HODL, even if the value of your portfolio increases. The taxable event is when you sell, exchange, or gift your crypto (to a DGR, in the case of donations).

- Buy and Hold: If you simply buy and hold your crypto, then you don’t need to pay tax on the cryptocurrency you HODL, even if the value of your portfolio increases. The taxable event is when you sell, exchange, or gift your crypto (to a DGR, in the case of donations).

- Selling crypto for fiat (AUD or other currency): Taxable – CGT event. When you sell crypto for dollars (or any fiat currency), it’s a disposal. Calculate your capital gain or loss as discussed: sale proceeds (in AUD) minus cost base. The timing is the moment of sale/trade execution.

- If you held the crypto >12 months before selling, you may get the 50% discount on any gain.

- If you held <12 months, the full gain is taxable.

- Any capital losses from other disposals can be used to offset the gain from a sale.

- If you held the crypto >12 months before selling, you may get the 50% discount on any gain.

Example: Dave bought 0.5 BTC for $15,000 in September 2023. He sells 0.5 BTC for $25,000 in August 2025. That’s a $10,000 gain. Since he held over 12 months, only $5,000 is added to his taxable income (assuming he has no losses to offset).

Trading Crypto-to-Crypto (Including Stablecoins & NFTs)

- Swapping one crypto for another: Taxable – CGT event. As mentioned earlier, trading crypto A for crypto B is treated as if you sold A for its market value and used that to buy B. So you incur a capital gain/loss on A based on its value at that time and your cost base for A.

- This applies to swapping into stablecoins too. Selling BTC for USDC or AUDT (AUD stablecoin) triggers CGT on the BTC.

- If you swap multiple assets (like using one coin to directly buy several different coins via some DEX), each instance is a disposal of the original asset.

- This applies to swapping into stablecoins too. Selling BTC for USDC or AUDT (AUD stablecoin) triggers CGT on the BTC.

- Using crypto to buy NFTs: This is essentially crypto-to-crypto trade. You disposed of cryptocurrency in exchange for an NFT. If the crypto you spent had gone up since you acquired it, you have a gain to report. The cost base for your new NFT is the value of the crypto you gave up.

- When you later sell that NFT, if you get crypto for it, that’s another CGT event (disposal of the NFT).

- NFTs are considered crypto assets by the ATO, so similar rules apply.

- When you later sell that NFT, if you get crypto for it, that’s another CGT event (disposal of the NFT).

- Swapping an NFT for another NFT or for crypto: Also a CGT event. It’s like bartering assets; you trigger gains/losses on what you gave up.

Key takeaway: Every exchange of value in the crypto world is likely a taxable event unless it’s purely a transfer of the same asset under your ownership. Many people get caught out by this – they might trade altcoins frequently, racking up gains and not realize each trade is reportable. Keep a log or use tracking software for every trade.

Spending Crypto on Goods and Services

Spending your crypto is convenient – some retailers accept direct crypto, and crypto debit cards let you spend via Visa/MasterCard networks by deducting your crypto. However:

- Spending crypto (not a personal use asset): Taxable – CGT event. The moment you use crypto to buy something, you have disposed of that crypto. The ATO says to treat it like you sold the crypto for its market value, then used the cash to purchase the item.

- You calculate gain/loss with proceeds equal to the value of the item (or crypto) you received in return.

- This can make everyday purchases complicated if done frequently – each coffee you buy with Bitcoin technically is a tiny CGT event (which is why most people don’t use crypto for daily purchases; also, generally crypto values fluctuate making it impractical).

- You calculate gain/loss with proceeds equal to the value of the item (or crypto) you received in return.

- Personal use asset exemption: There is a specific exemption (detailed in Section 6.1) that if the crypto was a personal use asset – essentially meaning you acquired it for the purpose of spending on personal items, and it was a small amount – then the gain can be ignored. But the conditions are strict: the crypto must be used for personal consumption quickly after acquisition. If you hold crypto as an investment and then later spend it, that crypto is not a personal use asset and you owe CGT on any gains from when you bought it to when you spent it.

- Example: Jasmine holds various crypto for investment. She uses 0.1 ETH to pay for a new phone. Since she originally bought that ETH as an investment and held it, the 0.1 ETH is not personal use. If that ETH grew from $200 to $400 in value since she got it, she has a $200 gain to declare, even though she just spent it on a phone.

- Example: Jasmine holds various crypto for investment. She uses 0.1 ETH to pay for a new phone. Since she originally bought that ETH as an investment and held it, the 0.1 ETH is not personal use. If that ETH grew from $200 to $400 in value since she got it, she has a $200 gain to declare, even though she just spent it on a phone.

- Crypto debit cards / gift cards: The ATO clarified that when you load up a debit card with crypto or purchase a gift card with crypto, that loading action is a disposal of your crypto (you’ve effectively sold it to top up the card). Same goes for using crypto via payment apps. So there’s no loophole to avoid CGT by using intermediary cards – the tax event still occurs at the point your crypto balance is converted or used.

In practice, if you occasionally spend small amounts of crypto on personal purchases and you acquired that crypto not as an investment but just to spend, you might fall under personal use (e.g., a traveler buys $500 worth of BTC to spend on a holiday, uses it all on the trip). But if you’re spending from your investment stash, expect to calculate gains.

Our advice: If you want to actually use crypto for transactions, either stick to small amounts that qualify as personal use, or be prepared for the record-keeping headache. Many seasoned crypto folks simply convert to AUD when they want to spend, to simplify taxes.

Gifting Cryptocurrency (Giving and Receiving)

- Giving crypto as a gift: Taxable to the giver (CGT event). When you give someone crypto (with no payment in return), the ATO sees it as you disposing of that asset at market value. So you must calculate a gain or loss just as if you sold it for that market price on that day. It doesn’t matter if you gifted it to your spouse, your friend, or your child – there’s no special family transfer rollover or anything for crypto. The only time gifting isn’t taxable to the giver is if the asset is a personal use asset under $10k (again, rare for crypto except maybe gift cards or small spending as earlier).

- If you have a capital gain on gifting, you’ll owe tax on that gain. If you have a loss, you can use the capital loss as usual.

- Be mindful if planning to gift a large amount of crypto – you might trigger a big tax bill for yourself. It could sometimes be better to sell crypto and gift cash (so the recipient doesn’t have the asset’s tax history tied to you).

- If you have a capital gain on gifting, you’ll owe tax on that gain. If you have a loss, you can use the capital loss as usual.

- Receiving crypto as a gift: Not taxable on receipt. The lucky person who gets crypto as a gift does not have to include anything in income at that moment. It’s like someone giving you shares or property – no tax at transfer. However, the recipient needs to know the original cost (basis) of that crypto to them for when they eventually sell it. Generally, for gifts, the cost base is the market value at the time of the gift (because that’s what the other party is deemed to have disposed at). If Uncle Joe just sends you 0.5 BTC out of generosity, make a note of the value on that day – that’ll be your starting point for CGT when you sell or otherwise dispose of it.

- Selling gifted crypto: When you later sell crypto that was gifted to you, you calculate gain/loss from the value when you got it (as that’s effectively your cost base). If you held it >12 months since receiving, you can qualify for the 50% discount on any gains.

So gifting is kind of a one-sided taxable event: the giver deals with tax, the receiver eventually deals with CGT when they sell. Keep records on both sides.

One more point: There’s no gift tax in Australia (unlike the US). So you don’t worry about a separate gift tax – just the CGT.

Cryptocurrency Donations (and Tax Deductions)

Donating crypto to a charity or cause can have tax benefits, similar to donating cash or shares:

- If you donate crypto to a registered charity that is a Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR), two things happen:

- You do not face CGT on any gain for that donation. The act of donating is a disposal, but the law provides an exemption so you don’t pay tax on any capital gain for assets donated to DGR charities.

- You can claim a tax deduction for the market value of the crypto at the time of donation (assuming you held the crypto for more than 12 months, the deductible amount is the market value without any CGT discount issues on your end – because you’re not paying CGT; if held less than 12 months, it’s still just the market value you can deduct).

- You do not face CGT on any gain for that donation. The act of donating is a disposal, but the law provides an exemption so you don’t pay tax on any capital gain for assets donated to DGR charities.

- Essentially, donating appreciated crypto can be very tax-efficient: you don’t get hit with CGT and you get to reduce your taxable income by the donation amount, as long as the donee is a DGR and you have a receipt, etc.

- If donating to a cause that is not a DGR (like giving crypto to someone in need directly, or to a foreign organization not registered here), that typically wouldn’t be tax-deductible, and the act might be treated like a gift (meaning you as donor still have to handle CGT because the exemption might not apply). So ideally donate to proper charities to make use of the tax incentive.

Example: You have 1 ETH worth $4,000 that you bought for $1,000. If you sell it and donate cash, you’d have a $3,000 gain to pay tax on, and then you’d get a $4,000 donation deduction. If you’re in a 37% bracket, tax on the $3k might be $1,110, and deduction saves $1,480 (37% of $4k), net benefit not huge. But if you donate the ETH directly to a DGR charity:

- No CGT on the $3k gain (so you save that $1,110 you would have paid).

- You still get a $4,000 deduction, saving $1,480 in tax.

- Win-win: the charity gets the full $4k value (they’d likely liquidate it tax-free too), and you got additional tax savings by not incurring CGT.

For philanthropy-minded crypto holders, this is a great strategy.

Note: Keep documentation of the donation (e.g., an acknowledgement from the charity of the crypto and value on receipt). Also be aware if donating large amounts, certain valuation rules might apply (for very high value gifts, >$5k, sometimes a formal valuation is needed, but usually market price suffices for publicly traded crypto).

Airdrops and Hard Forks

We touched on airdrops in section 4.1 under income, but here’s a summary:

- Airdrops (receiving free tokens): Typically treated as income at FMV on receipt (taxed as such, see 4.1). Once you hold them, any later sale is a CGT event with cost base equal to that income value (or zero if it was an “initial allocation” airdrop that wasn’t taxed initially).

- When you dispose of airdropped coins, calculate gain/loss from that cost base.

- When you dispose of airdropped coins, calculate gain/loss from that cost base.

- Hard forks (chain splits): When a blockchain forks and creates a new coin (like Bitcoin Cash forked from Bitcoin, Ethereum split into ETH and ETC historically, etc.), if you hold the original coin, you might suddenly have units of a new coin.

- The ATO’s stance for investors: The new forked coins are not taxed as income at the time of the fork. Instead, they are treated as having a cost base of zero (assuming you didn’t pay anything for them).

- No CGT event at the moment of the fork. But later, when you sell or swap the forked coins, it’s all gain (since cost base zero).

- You can, however, get the 12-month CGT discount on forked coins if you hold them over a year after the fork, because the gain is a capital gain.

- Example: You held 2 BTC and got 2 BCH in the 2017 fork. The BCH had zero cost to you. If you sold the 2 BCH for $1,000, that’s $1,000 capital gain. If within 12 months, full $1,000 taxable; if after 12 months, only $500 taxable (50% discount).

- If you’re a business, forked coins might be treated differently (as trading stock, possibly requiring a cost allocation or income recognition, but let’s focus on typical individuals).

- The ATO’s stance for investors: The new forked coins are not taxed as income at the time of the fork. Instead, they are treated as having a cost base of zero (assuming you didn’t pay anything for them).

- Token swaps (protocol migrations): Sometimes a project migrates to a new token (e.g., swapping all old tokens for a new contract token, or moving chains). Generally, if the old token becomes worthless and you get a new one, the ATO often considers that not a CGT event if it’s essentially just a technological upgrade. But if the old token retains value and you just got new ones, that could be seen as a fork (and might have CGT consequences). These situations are case-by-case and beyond our scope, but they exist.

In summary, airdrops often = immediate tax; forks = tax on eventual disposal with no initial hit. Always record dates and market values when you receive new coins via drop or fork.

Mining and Staking Rewards

Expanding a bit from earlier:

- Mining (already covered): Hobby mining – coins acquired, not immediate income, CGT on disposal. Business mining – coins immediately counted as income (and inventory).

- If hobby mining, the moment you mine a coin, note its market value – that’s effectively your cost base (some argue it’s zero if hobby and you can’t claim expenses, but logically the value when you “found” it is what you’d use as baseline).

- Personal use note: Mined crypto generally won’t qualify as personal use asset even if small; ATO specifically says personal use asset exemption rules don’t apply to capital gains made on the disposal of cryptocurrency acquired from mining or as a reward.

- If hobby mining, the moment you mine a coin, note its market value – that’s effectively your cost base (some argue it’s zero if hobby and you can’t claim expenses, but logically the value when you “found” it is what you’d use as baseline).

- Staking (Proof-of-Stake): The rewards (new coins) are income on receipt. You also might have your originally staked coins increase in value separately which is on capital account if you eventually sell them.

- Also, some staking involves lock-ups (like early ETH2). As mentioned, if you technically “earn” rewards daily but can’t access them yet, ATO hasn’t given clear rules. A reasonable approach is to perhaps treat them as derived only once you have control (like after the merge when withdrawals enabled). But to be safe, some might declare as they accrue. This is complex – consider advice for large amounts.

- Also, some staking involves lock-ups (like early ETH2). As mentioned, if you technically “earn” rewards daily but can’t access them yet, ATO hasn’t given clear rules. A reasonable approach is to perhaps treat them as derived only once you have control (like after the merge when withdrawals enabled). But to be safe, some might declare as they accrue. This is complex – consider advice for large amounts.

- Yield farming / Liquidity mining: These are essentially forms of staking in DeFi. If you provide liquidity and get reward tokens or extra yield, those new tokens or interest are income at the time you receive them.

- However, providing liquidity also usually involves a token swap: you deposit crypto into a pool and receive LP (liquidity provider) tokens. ATO’s guidance indicates that depositing into a pool in exchange for LP tokens is a CGT event (you disposed of your coins for the LP token). When you exit, trading LP tokens back for your coins is another CGT event. This means adding and removing liquidity can each trigger capital gains or losses, depending on asset values.

- Additionally, any yield or incentive token earned in the interim is income.

- DeFi can create numerous taxable events (trades, income, etc.). Keep detailed records if you’re active here.

- However, providing liquidity also usually involves a token swap: you deposit crypto into a pool and receive LP (liquidity provider) tokens. ATO’s guidance indicates that depositing into a pool in exchange for LP tokens is a CGT event (you disposed of your coins for the LP token). When you exit, trading LP tokens back for your coins is another CGT event. This means adding and removing liquidity can each trigger capital gains or losses, depending on asset values.

- Masternodes, Forging, etc.: Similar to staking – any block rewards or fees earned are income.

In short: if crypto just appears in your account because you did something (staked, provided service), count it as income (and then later capital for any appreciation after receipt). If you swap assets around in DeFi, count each swap as disposal.

DeFi, Liquidity Pools, and Wrapped Tokens

Decentralised Finance introduces complex scenarios:

- Lending crypto (DeFi or CeFi): If you lend out crypto and get interest paid in crypto, that interest is income (like bank interest) at the time you receive it.

- Liquidity pools & yield farming: (Already discussed above) – providing liquidity often triggers CGT due to token exchange, plus income from yields.

- Wrapped tokens (e.g., wrapping ETH to WETH, BTC to WBTC): The ATO has indicated that wrapping a token is considered a change of asset ownership – effectively a swap of the original coin for the wrapped version. So they treat it as a CGT event. (Swapping 1 ETH for 1 WETH at equal value might not create a gain if done immediately, but if your ETH appreciated since purchase, wrapping it would crystallize that gain for tax purposes.) Unwrapping back is another CGT event.

- This stance is somewhat controversial because economically wrapped tokens often just represent the same asset. But unless rules change, you should assume wrapping or unwrapping = taxable events and keep track of any differences in value.

- If possible, avoid unnecessary wrapping/unwrapping frequently, to reduce tax events (or do it in one go rather than multiple small transactions).

- This stance is somewhat controversial because economically wrapped tokens often just represent the same asset. But unless rules change, you should assume wrapping or unwrapping = taxable events and keep track of any differences in value.

Because DeFi taxation is evolving, the ATO’s 2025 guidance states that DeFi transactions may result in either capital gains events or assessable income, depending on the nature. When in doubt, consult resources or professionals. We anticipate rules to refine as DeFi grows, but at the moment treat each significant DeFi action as potentially taxable.

NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens)

NFTs exploded onto the scene, and the ATO considers them crypto assets as well:

- Creating & selling NFTs: If you create an NFT (like digital art) and sell it, how it’s taxed depends on whether it’s a hobby, investment, or business:

- If you’re an artist occasionally selling some pieces, it could be considered a hobby (which generally isn’t taxed) if it’s genuinely not for profit. But if it becomes regular and with a profit motive, the ATO may view it as a business. In that case, selling your NFTs is akin to selling any product and would be business income (taxed at your income rate, no CGT discount, but you can claim expenses related to production).

- Many digital artists likely should declare the income as business income to be safe (and then deduct any expenses).

- The buyer of your NFT will treat it as an investment (CGT asset) on their side.

- If you “mint and immediately sell,” you’re basically earning crypto from a sale – that’s income to you at the value of crypto received.

- Royalties from NFTs (some NFTs give creators a cut on secondary sales) are also income when you receive them.

- If you’re an artist occasionally selling some pieces, it could be considered a hobby (which generally isn’t taxed) if it’s genuinely not for profit. But if it becomes regular and with a profit motive, the ATO may view it as a business. In that case, selling your NFTs is akin to selling any product and would be business income (taxed at your income rate, no CGT discount, but you can claim expenses related to production).

- Investing in NFTs (buying and holding/trading): If you buy an NFT (with crypto or fiat), that’s an acquisition of a CGT asset. When you later sell or dispose of it, you have a capital gain or loss just like any other asset.

- Use the cost you acquired it for (in AUD) as your cost base. If you bought it with crypto, remember that use of crypto was a CGT event for the crypto as well.

- If you make a profit selling the NFT and you held it over 12 months, you get the CGT discount.

- If you incur a loss on an NFT sale, that’s a capital loss that can offset other gains.

- NFTs are often collectibles and some might wonder if they’re treated under the special “collectible” CGT rules (where personal collectibles under $500 are exempt). As of now, the ATO treats NFTs just like other crypto assets for tax – meaning the standard crypto rules apply, not the collectible rule.

- It’s unlikely an NFT would be considered a personal use asset unless maybe it’s something you bought purely for personal enjoyment and it’s low value – but generally, assume gains on NFTs are taxable.

- Use the cost you acquired it for (in AUD) as your cost base. If you bought it with crypto, remember that use of crypto was a CGT event for the crypto as well.

- Trading NFTs for NFTs: Like trading one artwork for another – a disposal of one (CGT event) and acquisition of another.

Given the novelty, it’s wise to record all NFT transactions carefully. The tax treatment aligns with crypto: gains = CGT, creation income = possibly business income.

Margin Trading, Futures, and Other Advanced Trades

Dealing with derivatives and leverage adds complexity, and the ATO’s guidance here is limited:

- Margin trading & leveraged positions: If you use borrowed funds to trade crypto (margin trading), any profit or loss when the position is closed will typically form a capital gain or loss on the asset traded. However, if such trading is frequent and business-like, profits may be treated as ordinary income for tax purposes. (Interest or fees paid for crypto loans might be deductible against those gains if they’re taxed as income.)

- Futures, options, and CFDs: Crypto futures, options, and contracts for difference (CFDs) are generally treated as speculative investments. The ATO has indicated that profits from these are often taxable as income (especially if you’re regularly trading them as a business). If you only occasionally dabble in futures or options, you might report gains as capital gains, but note that no 50% CGT discount would apply if the positions are short-term. In the absence of explicit ATO rules, tread carefully and keep records of your trades and outcomes.

- When in doubt: Given the uncertainty in how to categorise derivative gains (capital vs income) and the potential complexity of these instruments, it’s best to consult a crypto tax professional if you engage in significant margin or derivative trading. Getting the treatment right can affect both the tax you owe and how you can utilize losses.

Exemptions and Special Cases

Not every crypto transaction results in tax. There are a few instances where you can legally not pay tax on crypto. Let’s go through these special cases:

Personal Use Asset Exemption

The personal use asset rule is often misunderstood. It does exist for crypto, but applies only in very limited scenarios. By definition, a personal use asset is something you acquire and use mainly for personal enjoyment or consumption, and not as an investment.

For cryptocurrency:

- If you acquire crypto solely to buy something for your personal use or enjoyment, and you do actually use it for that purpose within a relatively short time, it could be a personal use asset.

- Also, the cost of the crypto must be less than $10,000 to qualify for the CGT exemption on personal use assets. (Assets above $10k aren’t exempt even if personal use).

- The ATO has explicitly said that the longer you hold crypto, the less likely it is to be personal use. If it’s stored or kept as an investment, it’s not personal use.

- Crypto used in a profit-making way (investment, in a business, for income) is not personal use.

Example: Steve wants to buy a concert ticket from a website that only accepts crypto. He doesn’t own any crypto yet. He goes and buys $300 worth of Litecoin, and two days later he uses that Litecoin to purchase the tickets. In this case, Steve’s crypto was a personal use asset – he acquired it to buy a personal item (the ticket) in the near term. Any small gain or loss during those two days is disregarded under the personal use exemption (and practically would be tiny).

- If Steve instead bought $5,000 of Litecoin, held it for 8 months hoping it would rise, then spent it on a holiday booking, that’s likely not personal use. Even though the end use was personal (holiday), the primary intent and the long hold suggest investment. He would owe CGT on any gain over those 8 months.

Takeaway: Unless you’re specifically buying crypto to spend soon on a personal purchase, assume your crypto is not a personal use asset. Most crypto investors will never qualify for this exemption except maybe in trivial cases (small purchases).

If you do have a case for personal use asset, document your intent (e.g., notes that “bought XMR to pay for VPN service next week”). The exemption can eliminate CGT on that specific amount of crypto.

Crypto Gifts & Inheritances

We discussed gifting from the giver’s perspective (taxable for the giver). For the recipient of a gift, it’s not taxed upon receipt. If you’re given crypto as a gift, that’s effectively an exempt transaction for you at that time. Just remember the cost base is the market value at gift time.

For inheritances (if someone passes away and leaves you cryptocurrency):

- Generally, when someone dies, their assets pass to beneficiaries with special tax rules. For CGT assets, there’s usually a rollover: the person’s cost base transfers to the beneficiary, and no immediate tax is triggered at death (for the estate or beneficiary) if the beneficiary is an Australian resident. The beneficiary effectively steps into the shoes of the deceased regarding cost and holding period.

- If you inherit crypto, you won’t pay tax until you later dispose of it. When you do, you calculate gain from the original cost base (if the deceased acquired after 1985 CGT regime; if they had it before CGT existed – unlikely for crypto since CGT in Australia started in 1985 and crypto didn’t exist – but generally pre-CGT assets inherited are treated as if cost base is market value at date of death).

- The 12-month holding period for discount: you can count the deceased’s holding period as well. So if grandma held Bitcoin for 5 years and you inherit it and sell a month later, you still qualify for the discount because combined held >12 months.

Thus, inheriting crypto doesn’t whack you with tax immediately. Just be aware when you sell it eventually, you might have a sizable gain depending on original cost.

Also, if you donate crypto to someone (gift) or leave it in a will, for the person giving (or their estate) it’s as if sold at market value at that time, so could trigger CGT in the final tax return of the deceased or the giver’s tax.

Transferring Between Your Own Wallets

Many crypto users have multiple wallets or exchange accounts. Thankfully:

- Moving crypto between accounts or wallets you own: Not a taxable event. As long as you haven’t changed beneficial ownership (it’s still yours), you’re just shifting assets around. The ATO has confirmed this.

- Be careful to keep records so you can show that the sending and receiving addresses/exchange accounts are both yours. That way if data shows a withdrawal here and deposit there, you can match them and show no sale occurred.

- You maintain the original cost base and acquisition date for the coins moved.

- Be careful to keep records so you can show that the sending and receiving addresses/exchange accounts are both yours. That way if data shows a withdrawal here and deposit there, you can match them and show no sale occurred.

- However – watch out for fees: If you pay a network transaction fee in cryptocurrency (like a gas fee in ETH or a Bitcoin miner fee) to transfer between wallets, that fee itself is a disposal of whatever crypto was used to pay it. So if you spent 0.001 ETH as gas, that tiny bit of ETH is considered sold. You may have a small gain or loss on it, which technically should be reported.

- In practice, these fee disposals are often very minor amounts, but if you made a large transaction with a high fee or you frequently move assets, those could add up.

- The cost base for the fee portion is whatever that portion of crypto originally cost you.

- Many automated tax software can flag transfer fees as disposals to include.

- In practice, these fee disposals are often very minor amounts, but if you made a large transaction with a high fee or you frequently move assets, those could add up.

Example: You send 1 BTC from Exchange A to your hardware wallet. You pay a 0.0001 BTC mining fee. That 0.0001 BTC is gone to a miner – treat it as disposed. If you bought that 0.0001 BTC originally for $5 and at time of transfer it’s worth $8, you’d technically have a $3 gain (not much, but just illustrating).

The 1 BTC itself, now in your wallet, is still under your ownership with the original cost base intact, and no CGT event on that portion.

So, moving crypto for your own custody or rebalancing between your own accounts is fine and not taxed – just carefully note any crypto spent in the process.

Crypto Prizes, Lottery Wins, and Gambling Winnings

As briefly noted:

- If you win cryptocurrency from a lottery, competition, or gambling context (like you won a poker tournament paid in crypto, or a radio contest giving 1 Bitcoin):

- The ATO has indicated such winnings are not taxed as income (mirroring how lottery and prize winnings in AUD are tax-free windfalls).

- But those coins are now an asset you own. So note the value at the time you won them (that’s effectively your cost base).

- When you eventually sell that crypto, any increase in value from when you received it is a capital gain.

- If their value dropped by then, that’s a capital loss you could use.

- The ATO has indicated such winnings are not taxed as income (mirroring how lottery and prize winnings in AUD are tax-free windfalls).

This is great because in some countries, certain prizes would be taxed, but in Australia, personal windfalls aren’t (except if you regularly engage in a skill-based prize as income, but that’s an edge case).

Gambling with crypto: If you use crypto to gamble and you win more crypto, it’s a messy area. Likely treat the net outcome – if you ended up with more crypto, that increase might be just considered part of gambling winnings (not taxed) at that moment. But any further use after that point triggers CGT on changes. Very niche, not common for ATO to parse personal gambling gains.

Keep evidence a win was from gambling or a prize (in case ATO wonders where you got the crypto without having paid for it).

GST on Crypto Transactions (Businesses)

Cryptocurrency is treated similarly to money for GST purposes in Australia. This means:

- Buying or selling crypto itself is not subject to GST (it’s a financial supply/input-taxed).

- If a business accepts crypto as payment for goods or services, it should charge GST (if applicable) on the value of the goods/services as usual (converted to AUD), just as if the payment had been in cash. The crypto payment itself doesn’t impose additional GST.

For most individual crypto investors, GST doesn’t impact your transactions. GST considerations are only relevant if you are running a business involving crypto sales or purchases, and these rules ensure there’s no double-taxation on the crypto itself.

Record Keeping and Reporting

Being in the crypto space often means dealing with numerous transactions. The ATO expects that you maintain proper records to back up your tax calculations. Here’s what you need to know:

Keeping Accurate Records (What the ATO Expects)

The ATO requires taxpayers to keep records for at least 5 years after the relevant tax return is lodged (or 5 years after an entry is made, whichever is later). For crypto transactions, you should maintain:

- Transaction dates for each crypto asset purchase, sale, swap, or transfer.

- Amounts in AUD for each transaction – either the AUD amount involved or the AUD equivalent (you may need to convert from USD or crypto to AUD using a reliable exchange rate on that day).

- Nature of the transaction – what it was (buy, sell, swap, income from staking, etc.) and the purpose (investment, personal use, business).

- Counterparty or source – for example, the exchange name, or the other party’s wallet (you might not know the person, but you have a wallet address or transaction ID).

- Records of any transaction fees paid in crypto or fiat.

- Receipts or invoices – if applicable (e.g., if you paid crypto for a service and got an invoice, keep it).

- Exchange account statements and wallet transaction histories.

In practice, this means you might have CSV files from exchanges, screenshots of wallet transactions, emails confirming trades, etc. It’s wise to use a systematic approach, because reconstructing this at year-end (or worse, years later during an audit) is painful.

The ATO explicitly states: “You can use an accountant or third-party software to help meet your record-keeping obligations and work out your tax.” Many Australians use crypto tax software or portfolio trackers to aggregate this information. The key is that if the ATO asks, you can present a clear ledger of all crypto transactions and how you calculated any amounts on your tax return.

Pro tip: Reconcile your records annually. For example, at the end of each financial year, list all the crypto assets you hold and their cost bases (and market values). Ensure that every change from the prior year is explained by a recorded transaction. This will catch any missing pieces.

Remember, records need to be kept for 5 years after you lodge the return that includes those transactions. If you lodge late, the 5 years starts from that later date. Keep records digitally and back them up, as exchanges can sometimes delist coins or even shut down (taking your history with them).

How and Where to Report Crypto in Your Tax Return

When tax time comes (typically July through October for individual filers), here’s how crypto-related items are reported:

- Capital gains/losses: Individual tax returns have a Capital Gains Tax section. You will declare:

- Total capital gains for the year (sum of all your gains before discounts).

- Total capital losses for the year.

- Net capital gain after applying losses and any discounts.

In the online myTax form, for instance, you answer “Yes” to having capital gains/losses, and you can input the numbers. You don’t necessarily list every trade; usually you provide a total (though you should have the breakdown available). If you disposed of only crypto and no other assets, you can summarize it all together. If you have many transactions, the ATO might accept a single net gain figure as long as you can provide the calc on request. - Important: Apply any carry-forward losses from previous years as well. There’s a field for prior year net capital losses.

- If your net result is a loss (with no gains to offset), you still declare the loss (so it can carry forward).

- Total capital gains for the year (sum of all your gains before discounts).

- Crypto income: This will go in different spots depending on context:

- Staking/airdrop/mining income (not business): Often declared under “Other income” (there’s usually an item for sundry income where this can be included). You might label it “cryptocurrency earnings (staking/airdrop)”.

- Crypto as business income: If you’re running a business (trader, mining operation, etc.), you would include the income and expenses in the business schedule of your tax return (under your ABN or in a company return as appropriate). For example, mining business would report crypto earned as business revenue (converted to AUD).

- Employment income in crypto: Should be included on your PAYG summary by your employer (often as salary sacrifice or fringe benefit if structured that way), but if not, you’d include it as normal salary or as “other income” with explanation.

- Airdrops (taxable ones): Also go in other income with description.

- Referral or bonus crypto: Also other income.

- Staking/airdrop/mining income (not business): Often declared under “Other income” (there’s usually an item for sundry income where this can be included). You might label it “cryptocurrency earnings (staking/airdrop)”.

- Foreign income designation: Crypto itself isn’t “foreign income” (it’s not a salary from overseas, etc.), but if you used an overseas exchange or earned staking income from an offshore platform, it’s still just part of your assessable income, not separately listed as foreign. There’s no separate category for “crypto” on the return, but the ATO does specifically ask if you disposed of crypto, in the capital gains section.

If you use an accountant, ensure you supply all this information to them. If you’re lodging yourself, double-check the ATO’s guidance (they often publish crypto tax info on their website around tax time, which can help with the specifics of filling out the form).

Also, note key labels: The net capital gain you compute (after losses and discounts) ultimately flows into your total income on the tax return. If you had only losses, those carry forward and nothing reduces your other income in the current return (again, unless you’re a business).

Key Dates and Deadlines (Australian Tax Year)

A quick refresher on timing:

- The Australian financial year runs from 1 July to 30 June. So, for example, the 2024–2025 tax year covers 1 July 2024 up to 30 June 2025.

- If you are an individual lodging your own tax return, the due date is generally 31 October following the end of the financial year. For 2024–25, that means 31 October 2025.

- If you lodge through a registered tax agent (and are on their books by October 31), you often get an extended deadline. Many individuals using tax agents have until 15 May of the following year to lodge, though this can vary (first-time clients or late prior returns might have shorter deadlines).

- For businesses (companies, trusts, etc.) deadlines vary by entity and situation, but often extend to Feb or May if using an agent.

For crypto specifically:

- Try to have your transaction records for the year in order shortly after 30 June. Crypto market prices can be retrieved for conversions if needed, but it’s easier if you export your data close to year-end.

- The ATO has been known to send reminder letters in July/August to known crypto investors to nudge them to report correctly. Don’t ignore these; if you’ve done the right thing, no worries, but if you overlooked something, consider amending.

- If you realize after lodging that you made a mistake (maybe you forgot about a wallet or miscalculated something), you can and should amend your return. It’s far better to correct an error proactively than to wait for the ATO to detect it. Voluntary disclosures can result in reduced penalties.

Keep in mind also:

- Crypto record retention: As mentioned, keep records 5 years after the return. If you had a transaction in 2021–22, and you lodged in Oct 2022, keep those records until at least Oct 2027.

- If you have an ongoing stream of crypto activity, you might as well keep all records indefinitely in a well-organized archive, because each year new transactions come in and you may need past cost bases.

By staying on top of deadlines and keeping thorough records, you’ll find that tax time becomes much less stressful, even if you have a high volume of crypto trades.

Legal Ways to Reduce Your Crypto Tax

Taxes may be inevitable, but there are legitimate strategies to minimise how much you pay on your crypto profits. Here are some key ways Australian crypto investors can optimize their tax position:

Long-Term Investment and the 12-Month Rule

As discussed, holding your crypto investments for at least 12 months before disposing can slash your taxable gain in half (for individuals and trusts). This is one of the most powerful tax-reduction tools:

- Plan your trades: If you believe in an asset and can afford to hold, aim for that one-year mark to qualify for the 50% CGT discount on any gains.

- This doesn’t mean you should ignore market conditions (tax is just one consideration; don’t hold a crashing asset purely for tax reasons), but all else equal, a long-term approach is rewarded in the tax system.

- Note: the 12-month rule doesn’t apply to short-term traders or businesses. It’s meant for investment assets.

Long-term holding aligns with many crypto believers’ strategy (“HODLing”), so taxwise it reinforces patience. Plus, fewer trades also mean fewer events to calculate and potentially less tax from frequent short-term gains.

Offset Gains with Losses (Tax-Loss Harvesting)

If you have crypto assets that have performed poorly or become worthless, realising those losses can be beneficial:

- Tax-loss harvesting is selling assets at a loss to use that loss against other gains. If you have big gains in one asset but also hold some losers, selling the losers before end of financial year can reduce your net gain and thus tax.

- Important: Only do this if it makes economic sense. Don’t sell a good asset just for a paper loss (that wouldn’t be a loss then anyway). Focus on assets you are okay parting with or can rebuy later if you truly want (but watch wash sale rules as mentioned).

- Crypto markets often see rotations – you might sell one coin at a loss and put the remaining funds into a different coin you have more faith in. This way you maintain market exposure but also captured a deductible loss.

- If you got rug-pulled or a coin went to zero, you may be able to claim a capital loss even if you didn’t technically sell (in cases of asset becoming worthless or inaccessible, the ATO can allow a capital loss if you have evidence of the loss in value or that it’s irrecoverable).

- Example: an exchange collapse where your crypto is gone – you might claim a capital loss equal to the amount that became irrecoverable.

- Example: an exchange collapse where your crypto is gone – you might claim a capital loss equal to the amount that became irrecoverable.

Always use losses as soon as possible. If you have carryover losses, be sure to apply them to any new gains.

One caution: If you have overall losses and no gains, don’t try to “create” gains just to use losses; that’s not beneficial because using a loss only saves you the tax on a gain, it doesn’t get you a refund beyond that. Instead, carry forward the loss.

Timing Your Trades (Financial Year Strategies)

Timing can make a difference:

- End of Financial Year (EOFY) Planning: If you have flexibility on when to take profits, consider the tax year cutoff:

- Selling on July 1 instead of June 30 pushes the tax liability into the next financial year, giving you up to 12 more months before that tax is due and possibly putting it in a year where your other income is lower (maybe you’ll stop working, etc.).

- Conversely, if you have a bad year with a lower income, it could be a good time to take some profits because you might be in a lower tax bracket, thereby incurring less tax on that gain.

- Selling on July 1 instead of June 30 pushes the tax liability into the next financial year, giving you up to 12 more months before that tax is due and possibly putting it in a year where your other income is lower (maybe you’ll stop working, etc.).

- Consider your total income: If you expect a big income event one year (like a property sale or a work bonus), you might avoid adding crypto gains in that same year if you can wait, to prevent jumping brackets.

- However, don’t let the tax tail wag the dog: Only defer gains if market conditions are favorable or neutral. If your asset is at a high in late June and you think it might drop, it could be wiser to sell and pay the tax rather than hold just to save some tax while the market moves against you.

The key is to integrate tax planning with your investment strategy:

- If you were anyway going to sell in the short term, doing it just after June 30 can be slightly beneficial.

- If you have the luxury of time, aligning sales in years where you have less other income (e.g., a gap year, or if you retire) can reduce the effective tax rate on those gains.

Keep an eye on potential future tax changes too (e.g., if the government was to change rates or rules from a certain year, you might choose to realise gains earlier or later accordingly).

Using Structures like SMSFs and Trusts

Advanced planning might involve holding crypto through different entities:

- Self-Managed Super Funds (SMSFs): SMSFs are allowed to invest in crypto (provided the fund’s investment strategy and trust deed allow it, and you adhere to rules like the sole purpose test and separation of assets). The major advantage:

- SMSF tax rate is only 15% on investment earnings (including capital gains).

- If the SMSF holds a crypto asset for more than 12 months and then sells, it gets a 1/3 discount on the gain, effectively taxing the gain at 10%.

- If the SMSF is in pension phase (paying out retirement benefits to you and possibly tax-exempt on earnings), capital gains could even be 0% (subject to transfer balance caps etc., but that’s beyond this scope).

- Compare this to an individual potentially paying up to 45% on short-term gains or ~22.5% on discounted gains at top bracket – the difference is huge.

- Downside: your money is locked in super until retirement (typically age 60 or later for access). And SMSFs have costs and compliance requirements.